In 1852, the clipper Ticonderoga sailed from Liverpool to Port Phillip. Of the 795 passengers on board, 100 perished during the voyage and a further 68 while in quarantine. A number of factors led to the unprecedented loss of life, including the ship's design, the route chosen and the number of passengers, especially young children, on board.

This is a summary of the journey as it applies to our highland Scots. For a full account see Mary Kruithoff's excellent book Fever Beach: The story of the migrant clipper 'Ticonderoga', its ill-fated voyage and its historic impact, QI Publishing, Mount Waverley, 2002. Another good resource is the Ticonderoga website by Julie Ruzsicska <http://www.mylore.net/Ticonhome.html>.

The Ship

The Ticonderoga was a three-masted American 'double-decker' ship. It was a clipper used to carry cotton from the United States to England, and English emigrants to the US on the return leg.

After winning a contract to carry emigrants to Port Phillip in Victoria, captain and part owner Thomas Boyle had the ship fitted out for its first (and only) voyage to Australia. The fitout met or exceeded all existing regulations, with Captain Boyle adding additional facilities for the comfort of his passengers.

The upper deck had the single women's area and a married area. The lower deck had another married area and the single men's area. Ships officers and crew had separate areas at each end of the upper deck. The male hospital, female hospital and men's ablutions areas were all on the upper deck. Sanitation was good on the upper deck but poor on the lower where they only had 'night utensils'.

Two doctors were employed, Dr Joseph Sanger was surgeon superintendant and Dr James Veitch was his assistant.

Captain Boyle catered well for the voyage with ample provisions - food, water, medical supplies, etc. - for all but the most extreme voyage.

The Journey

The official start of the journey for highland Scots was when made their own way to the emigration office at Glasgow. From there they were transported over 350 km down the UK west coast by packet steamer to the port of Liverpool. A ferry then took them across the Mersey river to the emigration depot at Birkenhead.

While at the depot, every passenger underwent an inspection to ensure their suitability for travel and for work in Victoria.

On Wednesday 4 August 1852, 795 migrants, predominantly highland Scots, boarded the Ticonderoga and began their voyage to Port Phillip in Victoria.

As they left their homeland forever, few had work lined up in Victoria, and none would have known what was in store for them during the voyage.

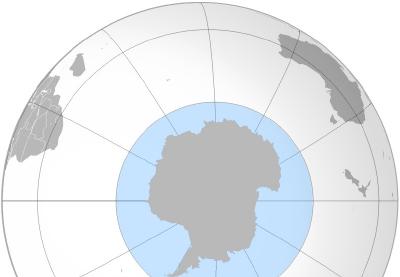

The route took them down the west coast of Africa, then generally east to Victoria. But rather than travel due east, they followed a 'Great Circle' route. Great Circle sailing is most easily understood by referring to the map below of the Southern Ocean (in blue). It can be seen that the shortest route between the southern tip of Africa (on the left of the map) and Victoria, is not due east (which would follow the curved line) but one which passed through the Southern Ocean.

Although great circle sailing was more difficult to navigate, it significantly reduced the duration of the journey and so was preferred by the ships' owners and their captains. However, sailing through the freezing waters and big ever present storms, played a large part in the huge loss of life.

Over the next few weeks, the passengers settled into their routine of waking bells, cleaning, meals, more cleaning, schooling (reading, writing and arithmetic) and lights out at 10 pm. There was also religious service on Sundays. The single women were segregated from the others, and their quite separate lives under the control of a matron, also included sewing and bible study.

Dr Sanger reported disease about two weeks into the voyage with the first death on 12 August. This and several that followed were babies and young children, and due to malnutrition, pneumonia and diarrhoea. The first death due to fever was that of a 16 year old girl on 23 August. By October, with storms, icebergs and fogs in freezing Southern Ocean regions, raging epidemics of typhus and scarlatina (scarlet fever) resulted in several deaths every day. As families huddled together for warmth, they unwittingly encouraged the spread of typhus, as it was not known until about fifty years later that it was transmitted by body lice.

By the end of October, over three hundred passengers and crew were sick with a variety of illnesses, the hospitals had overflowed, medical supplies had run out, and the two doctors were exhausted with Dr Sanger showing typhus symptoms. As cleaning routines had broken down, especially on the lower deck, the ship was in the most hideous state imaginable.

Land at Last

When 'Land ahoy!' was called from the crow's nest on 1 November after 90 days at sea, the sense of relief and hope must have been overwhelming. The ship had arrived at Port Phillip heads, and two days later moved to what is now called Ticonderoga Bay on Point Nepean, the site of a proposed quarantine station. This place was chosen to drop anchor due to fears of taking so many people with deadly fever on to Melbourne.

With no facilities other than what they brought with them on the ship, the mammoth task of evacuation began by moving the sick and dying to makeshift shelters on the beach. Urgent messages were relayed to officials in Melbourne and before long supplies began to arrive by land and sea. Arriving with the first supplies the following day was a Dr Taylor who had accepted the offer of taking charge of the situation and in doing so, establishing the quarantine station.

Over the following weeks, all passengers and their belongings were moved to the beach, cooking and sanitation facilities were set up, the ship was stripped and cleaned, and a second hospital ship was established. It was hot, so bodies were buried quickly. The able-bodied started to work on parts of the new quarantine station, schooling was established, and every effort was made to occupy the large number of increasingly restless passengers.

On Sunday 19 December 1852, when he was satisfied all crew were fully recovered, Dr Hunt (Health Officer of Port Phillip) gave the all clear for the Ticonderoga to be released from quarantine. A further 68 people had died during quarantine. On the morning of Wednesday 22 December, the ship left Point Nepean, arriving in Hobson's Bay later that day. Scaremongering on the wharves meant that no one would row them to shore for two more days, so the first passengers were taken the 12 km to Queen's Wharf on Friday 24th, Christmas Eve. By then making their way to the Immigration Barracks near the corner of Spencer and Collins streets, their journey had officially ended.

The Immigration Barracks also served as a labour exchange. The single women were employed straight away and most of the others found well paid work quickly. By mid-February, there remained in the barracks thirty widows, orphans and unplaced families.

Aftermath

The death toll of 168 was double the highest of previous emigrant ships. There was a very high death rate for adults (82) and fifty-eight families lost at least one parent. Around 80% of children under one year old who were taken on board at Birkenhead died before their families landed at Queen's Wharf.

When news of the Ticonderoga disaster reached England in early February 1853, an enquiry was soon held. The Land and Emigration Commission then advertised that no double-deck ships would be used again, and no more families with more than two children under seven years or three under ten years would be accepted for emigration.